It's been two years since I lost my dad. Two years since I learned what it means to lose someone you truly love and who loves you. It means this: it's been two years since I've seen my dad, heard his voice, shared the joy in my life with him, seen him laugh, given him a hug. It doesn't really get better; it gets different. It arguably gets worse, because I miss him two years more than I did before. It is so much worse than I could have imagined.

Ever since it happened I thought I should write a post about what I learned about dealing with cancer and death. Maybe there's something I could say to help someone who reads this. For family, friends, and for the person dealing with their own death, it is really hard to know what the right thing to do is. There are definitely things to do, say, or not say that can make a difference in how everyone feels after the fact. My "lessons" might not apply to everyone, and applying many of these lessons can be very challenging, but I wanted to give something to the people navigating a terrible diagnosis for the first time. Something like this might have helped me at the time. It's hard for people who have gone through it to share it with you, either because they don't want to or can't remember it, or because they believe each situation is too unique for their help to apply. And when you're going through something like this, you don't exactly have the time, energy, or desire to run out and buy a self-help book. So maybe this can help someone.

*** Don't feel obligated to read the rest of this. Maybe it's enough to just know that it's here in case you or someone you know needs it one day. I hope you never need it.

July

My dad turned 61 on Friday, July 16th. The next Monday evening, when I was still at work late, I got a call from my mother, hysterically crying because

my dad had just been diagnosed with a tumor in his brain. I was at the hospital the next day when the doctor told us it was kidney cancer in his brain, lungs, and his one kidney. I remember calling him on his birthday and I remember how depressed he was to be turning 61. I also remember how much he wanted to turn 62 when he was diagnosed just a few days later.

Lesson 1 (for patients and caregivers): You have to remain ever vigilant about your health and the health of your loved ones. My dad first had cancer in 1998 and got a "clean bill of health" in 2003 at the cancer 5-year mark. This is just a statistical line though. Cancer can come back 10 or 20 years later. Other diseases can arise as well. You have to go for regular checkups and blood tests and always report any strange symptoms to your doctor. You should ask your loved ones when they last went for a checkup and ask about the details of the checkup. I'm sorry if that's an awkward conversation to have, but please consider the alternative.

This is the most important lesson. Despite all my other advice, often the only thing that can save someone is early diagnosis.

Lesson 2 (for the patients and future patients): One of the best gifts you can give to people who love you is to live your life with happiness. When someone loves you, your suffering is their suffering. It is not easy to be happy. It is not easy! But it's not selfish either. It's a gift to those around you.

Lesson 3 (for supportive friends): Complaining about old age and wrinkles and aches is insensitive. It's a stab at all the people personally dealing with health problems or who have family members who died young. Especially in this day of Facebook, you don't know what the person reading your complaint is going through in their life. I'm not trying to pass judgment on complaining-- goodness know I complain about all sorts of meaningless things-- I am asking you to be cognizant of the suffering all around you. Being old is like being rich.

Kevin and I had been hoping to get pregnant, but when my dad got sick we figured it wasn't going to happen after all this month. The morning after I returned from the first hospital visit, I got so dizzy I almost passed out. I figured it was the stress of the event, but now I think it could have been an early pregnancy symptom.

August

While

visiting the Soward Family I started to suspect that something was amiss, and as I got more and more tired in the following week, I finally took an early test that confirmed

I was pregnant.

Dad got brain radiosurgery, a noninvasive but traumatic outpatient procedure. He had the choice to try this before resorting to regular brain surgery, and it was very tempting because it was noninvasive. But regular brain surgery had a better chance of being effective and doing so more quickly, so in retrospect in might have been a better though more frightening choice. He was also put on medication to prevent post-op seizures.

After the radiosurgery, Dad developed a lot of leg pain, and it turned out that the hospital never scanned his arms or his legs and he had tumors in both. They offered him an

embolization for the tumor in his leg.

Lesson 4 (for the caregivers): This is a hard one. If your loved one has a life-threatening illness, you need to become a part-time specialist and nurse. The doctors will resist you in this endeavor, but the truth is that doctors and nurses have a lot of patients and make a lot of mistakes. When your loved one is diagnosed you need to ask for the primary sources of their diagnosis. I should have asked for his body scans. As soon as he had leg pain, I would have known they hadn't scanned his extremities. Instead, I assumed that they had, and that my dad had some unrelated pain. Preventable mistakes happened over and over again. You should read medication prescriptions and doses yourself and not just rely on the nurse's explanation. If at any point any doctor or nurse exhibits confusion on any topic, you need to follow up and personally understand what the confusion is. You need to ask about the risks of every single procedure. The doctors don't always volunteer that information because they feel like they have already weighed the potential risks for you, but they might lack some of the information about your loved one that you possess.

You need to do this yourself. It's not a job that can be passed on to others, because it's not just about being effectual, it's also about self-forgiveness and knowing you did all you could. I am not saying that you are likely to save your loved one by doing all this. Obviously the doctors are more qualified to do that. But you can save your loved one a lot of discomfort and save yourself the resulting heartache and guilt.

The end of August was truly awful. Chrissy's mom passed away from cancer. Due to my dad's brain radiosurgery he was on antiseizure medication, but the doctor made a mistake on his prescription and because of that

he had a seizure on a Thursday, and he again lost his ability to speak or walk. The doctors advised us to up his antiseizure medication and wait for him to improve again. (See above, check the medications and prescriptions.)

The next Friday after my dad's seizure, I stayed at my parents to help my dad while my mom went out. I two memories that stand out from that day: being grateful that I could make my dad a sandwich at lunchtime, and that he handed me one of his pillows when I sat next to him on the bed. He didn't even know I was pregnant yet, but even in his pain and sadness, he was thinking about me.

Lesson 5 (for the caregiver): Honoring your loved ones is a gift to yourself even more than it is a gift to them. The simple act of making a sandwich or fluffing a pillow is a benediction.

That Saturday, my mom told me that dad was getting worse, so I encouraged her to call an ambulance to

bring him to the hospital. The doctors said we couldn't wait any longer to see if the brain radiosurgery would work, so he'd have to get

regular brain surgery. The day of the surgery was one of the worst days in my life, and definitely the worst day of dad's life. We followed dad all the way to just outside the operating room, and when mom stepped out right before dad went in, I told dad I was pregnant. He couldn't speak, but reached out and kissed my hand and cried. He was eager to talk about it when he regained his speech a month later.

Lesson 6 (for the patient and caregiver): It seemed like the right choice to get the noninvasive radiosurgery instead of skipping to the invasive regular brain surgery, but when you're dealing with a very advanced disease, you should seriously consider aggressive interventions. Obviously the interventions themselves pose a risk, especially in terms of potential infections, but the disease might pose a greater risk. You also need to consider how the intervention will affect quality of life if the person turns out to just have a short time to live. Facing that possibility is one of the hardest factors to take into consideration because you just don't want to admit to yourself that your loved one might die, and that it might happen very soon. In our case, if we'd been psychic, we would have skipped to the invasive brain surgery, not because it ultimately saved his life, but because the intervention improved the quality of life for my dad in his final months.

Lesson 7 (for the caregiver): I definitely felt bad for myself (and for my dad) because I was going through my first pregnancy while my dad was dying. It's supposed to be a happy time, and even though the pregnancy itself made me happy, in many ways it was the worst time of my life. But I went on babycenter.com and there were tons of people who had lost loved ones while pregnant. There were even women who had lost one parent while pregnant the first time, and the other while pregnant the second time. There are even women who are themselves diagnosed with cancer while pregnant. There is unspeakable sadness everywhere.

Lesson 8 (for the caregiver): I'm not sure what the exact lesson here is, but I don't think I should have told my dad about my pregnancy before he went into the brain surgery. I did so because I was afraid he might not come out of the surgery, or that he might not come out of it himself, which thankfully he did. But I should have told him either way in advance or when he had started to recover significantly. He was very emotional when I told him, and his blood pressure was unusually high during the surgery. Perhaps he was just scared during the surgery, but I would have felt awful forever if something had gone wrong because I stressed him out before the surgery.

I was glad that we took him almost all the way into the surgery, and waited with him until the prep team took him, because the wait can be very long for a surgery even after the patient is taken out of his or her room. I'm glad he didn't have to spend that time waiting alone.

September

Dad moved to rehab after the brain surgery, and started speaking again little by little. Things were extremely tough for him. He kept saying the rehab was really hard, and I was confused because my dad regularly ran 15-18 miles a week. I tried to encourage him, but in retrospect, pushing him was not what he needed. He needed a less intensive physical therapy to be more comfortable, but we had picked this facility because it had the best speech and cognitive therapy.

Ash and Janice visited that weekend to try to cheer me up. They said I could still keep doing what I was doing, but what I was doing was spending all my free time with dad, and that didn't seem possible with visitors. I felt a little out of sorts not being with my dad that weekend. But overall, they did the best thing friends can possibly do, they came to physically offer their help and solace.

Lesson 9 (for the supportive friend): Don't just ask, "What can I do to help?" Offer specific things to help. Offer to come in person to see your friend at home or at the hospital. Send food. Send cards. Offer rides. I was so lucky to have amazing friends that did these things. Not just Ash and Janice, either. Some of my mothers friends were regular visitors in the hospital. Kevin was especially amazing throughout the illness. He educated himself on the disease, spoke to the doctors frequently, asked a lot of questions, and stayed with my parents even when I couldn't be there. I haven't forgotten what each person did for me during that period of my life, and I probably never will.

My dad was in aggressive rehab when his leg pain increased. The doctors decided to perform

a second leg embolization because the leg tumor had grown again. The first embolization was done with wires and this second one was done with alcohol, and they used a dye that possibly encouraged my dad's kidney to fail. I was worried and driving back and forth from Long Island was hard, so I took some time off work and joined my parents at the hospital every day. (This is Lesson 4 all over again. We should have asked in detail what the risks and side effects were of the leg embolization. We assumed the doctors understood the risks to his one kidney, but because these particular doctors were specialized in leg embolization, they seemed to ignore an otherwise minor risk to the kidney.)

Kidney failure would be fatal for my father because without a functioning kidney his cancer medication wouldn't work. Kevin and I had been waiting until after our next appointment to tell our mothers that we were pregnant (I had already told my dad), but the circumstances were scary enough that I thought it would be best to tell my mother on Monday night so that she could enjoy the news with dad.

Dad started his dialysis on Monday. This time we did ask about the risks in advance because by now we had learned our lesson. We insisted the doctors be specific because in the previous procedures any negative consequence that he could suffer, he did suffer. The doctor thought we were being crazy. He listed some potential risks and we considered it and then approved the procedure. We begged him to be careful. It was a complete nightmare because he had a rare allergic reaction. It was so rare that the doctor had not even mentioned that it was a possibility. They only had an alternate treatment available because 1 other woman had the same reaction somewhat recently. He did okay with the alternate treatment but he was still having trouble recovering from the allergic

Afterward the dialysis, he started feeling a little better than he had during the weekend, and mom was in okay spirits. So I told my mother right then that I was pregnant. She started crying and hugging Kevin and didn't let go, until I insisted on my turn for a hug. Dad pretended to be surprised, but I busted him. I showed mom the sonogram picture, but dad was interrupted by a follow-up ct-scan, so I showed him the following day after his second dialysis treatment. His

kidney started working again on its own by the end of the week.

Dad went back to rehab.

October

Dad was in rehab and fighting cancer when he

got an infection. After a few days at the hospital they were trying to release him, but my mom and I argued that he was not better and it turned out he had a

blockage in his kidney. So then he had a

kidney-bladder stint surgery we had been hoping to avoid.

Lesson 10 (for the patient and caregiver): This one is very specific. Getting an infection especially while in rehab is really common. Not all people in rehab are suffering from cancer or immune disorders so preventing infection might not be on the staff's radar in the same way it is in a hospital. Since someone with cancer already has a weaken system from fighting cancer and often also from the cancer treatment, and because an infection delays cancer treatment, getting an infection can be fatal. It is very important to do everything possible to avoid infection including alerting staff about the risk and trying to monitor as much as you can yourself.

While this was going on,

Kevin's mom visited, and now that I was 3 months along,

we told her I was pregnant. She was super happy. We also showed all our parents a videotaped sonogram of the baby. I had to work that weekend, both at the hospital and at the office. Ugh.

Dad came home from rehab and we had dinner together in Ramsey. He couldn't really enjoy his meal, but it was our last dinner all together at the table.

November

I was

4 Months pregnant, I felt the baby move, and I had a sonogram where the doctor couldn't see much, but guessed the baby was a boy. My dad continued to think I was going to have a girl, maybe because he was used to my mom, me, and my mom's friends, and he couldn't imagine not being surrounded by women.

Dad got his final procedure, and probably the one I regret the most, his

leg radiation. It didn't work and it seemed just to cause him more pain. After the radiation, we found out that he didn't have much time left because his

calcium was increasing and his tumors were growing larger.

I was lost in a mix of denial and grief and wasn't able to properly say goodbye.

Dad passed away on the morning of November 21.

Lesson 11 (for the caregiver, but also for the patient): Knowing when to say goodbye is one of the hardest things you'll ever face. You want to be hopeful. How can you encourage your loved one if you're saying goodbye? We had so many scares particularly the week that his kidney failed that I felt like we would pull out of the calcium increase as well because he was receiving medication for it. Doctors won't be clear with you. But there will come a moment when it's too late-- and that moment might come suddenly and unexpectedly so you need to try to say something to your loved one. Something to hold on to afterwards.

If you can do nothing else, then you have to hedge your goodbye. Something like, "If I lost you, I would miss you so much forever. I hope you know how much I love you. You are a wonderful father/mother/etc. I don't want this to be goodbye." Saying goodbye can be very painful, but not saying goodbye can hurt a lot later as well.

Lesson 12 (for the patient and the caregiver): One sure sign that this is your last chance to say goodbye is if the doctors start a high morphine drip to control pain. Again, this is not something the doctors will necessarily explain to you ahead of the fact. At certain levels the patient can no longer stay awake or communicate. The last thing you want to do is cause your loved one pain by taking them off the morphine drip, so you need to say goodbye before the drip is increased to sleep-inducing levels.

We spent

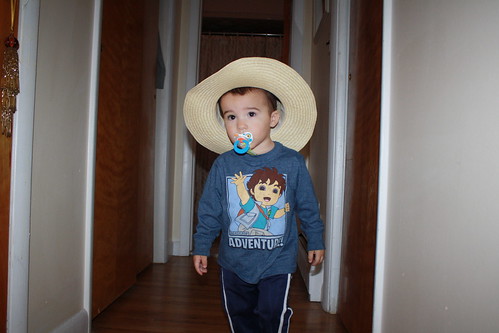

Thanksgiving with my mom sitting on her bed. At 20 weeks we went to the sonogram that told us the baby's gender. My mom came with us, and she cried when the doctor said it was

a boy. She already knew that we planned on naming the baby after my dad if the baby was a boy.

Lesson 13 (for the caregivers): Consider honoring your loved ones while they're still alive. Before he got sick, I actually did try to change my middle name to Shute (my dad's last name) when I got married but it wasn't a straight-forward process and I was told I had to go to court to do it. I never got around to it, and he wasn't alive to see me name my son after him either. I was lucky that my mother told him I was going to, but it's not quite the same.

Lesson 14 (for the caregiver): Forgive yourself and your loved one as soon and as completely as you can. Ultimately, nothing we could have done would have saved him because his cancer was much more aggressive than we realized. It took him in just 4 short months. There is no point in holding on to anger. There is no point in going to war with the universe. When you're ready, try to be as happy as you can be. Your loved one would want you to be happy, not unhappy. The love they gave you is still there, and it is powerful enough to lift you up if you let it.

My dad and I at my wedding.

Have a happy healthy Thanksgiving. Enjoy your family, and love them as hard as you can.